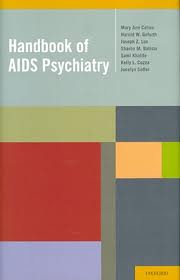

Handbook of AIDS Psychiatry by Mary Ann Cohen, Harold W. Goforth, Joseph Z. Lux, Sharon M. Batista, Sami Khalife, Kelly L. Cozza and Jocelyn Soffer, Oxford University Press, New York, 2010, 384pp, $49.95

Handbook of AIDS Psychiatry by Mary Ann Cohen, Harold W. Goforth, Joseph Z. Lux, Sharon M. Batista, Sami Khalife, Kelly L. Cozza and Jocelyn Soffer, Oxford University Press, New York, 2010, 384pp, $49.95

Book Review originally written for and published in the Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry

It is unusual for the Book Review Editor of this journal to request a review about a book that does not have psychoanalytic theory, dynamic psychiatry or the application of these ideas, as it’s main thesis. This book, which is about all aspects of AIDS, is such an exception. It is fitting that it be presented to the readers of this journal since this disease, more than any other modern day medical condition has impacted all aspects of psychiatry and mental health. Those of us who were practicing in the early 1980s, especially if you were doing hospital consultations, first saw this become known as a mysterious disease with dark spots on skin that was universally fatal. It then became associated with homosexuals and drug addicts The disease was believed to be highly contagious and caused by blood and sexual transmission. Medical personal became fearful of contracting the disease from patients. An accidental needle stick while drawing blood or being nicked with a scalpel during surgery, which once was an inconvenience, now became a potentially fatal event. The disease weakened the immune system and could lead to deadly opportunistic infections. It ultimately was identified as being caused by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). From it’s discovery in 1981 to 2006 AIDS killed more than 25 million people and is still counting.

Not only did psychiatrists and mental health professional see the impact of this disease in our hospital work but those of us doing outpatient psychotherapy could not help but appreciate the effect of this pandemic on many of our patients. Homophobias, which could be multidetermined at any point in time, became greatly exaggerated because of fears of contamination from AIDS. There was a reexamination of all sexual behavior as people began to realize that heterosexual transmission of this disease was also a reality. Questions were being raised whether couples should exchange HIV testing results before engaging in sexual relations? Then there was the realization that AIDS was devastating the gay and bisexual community. We saw a grieving response that extended beyond immediate close friend and families. People throughout the country visited exhibits of traveling AIDS quilts with patches made as a memorial to individual patients. There were forensic issues encountered by some of our colleagues where people were acting out their anger about being HIV positive by having unprotected sex . There were discussions among therapists of how to deal with a patient whom they knew was HIV positive but was not telling his or her partners.

The NIH and the NIMH awarded huge amounts of grant money directed towards AIDS and HIV research in the past 25-30 years. As a result many of the psychiatrists practicing today were supported by these grants at some time in their career or were trained by people who had such support and were well oriented about the psychiatric and psychological aspects of AIDS.

All of this is what makes this 2010 first edition of the Handbook of AIDS Psychiatry such a valuable book. Psychiatrist Mary Ann Cohen, a pioneer in the AIDS field and her six outstanding colleagues have written a book, which includes just about everything we should or might want to know about HIV and AIDS. It is billed as a practical book, which it is, but it is also a definitive work on this subject with over 1500 references. Some of the chapters are adapted from an earlier book titled Comprehensive Textbook of AIDS Psychiatry edited by Drs. Mary Ann Cohen and Jack Gorman, published in 2008 also by Oxford. Seven of the contributors to the earlier work took on the task of developing this current book.

such a valuable book. Psychiatrist Mary Ann Cohen, a pioneer in the AIDS field and her six outstanding colleagues have written a book, which includes just about everything we should or might want to know about HIV and AIDS. It is billed as a practical book, which it is, but it is also a definitive work on this subject with over 1500 references. Some of the chapters are adapted from an earlier book titled Comprehensive Textbook of AIDS Psychiatry edited by Drs. Mary Ann Cohen and Jack Gorman, published in 2008 also by Oxford. Seven of the contributors to the earlier work took on the task of developing this current book.

This is not an edited book. All the 14 chapters are written by some combination of the seven authors. Dr. Cohen was involved in all but two of the chapters. Drs. Battista and Soffer were listed as residents at the time the book was published. The first 13 chapters were each followed by multiple pages of references and the final chapter on resources had addresses, phone numbers and web sites.

The widespread imprint of this disease and the comprehensive approach of this book is illustrated in the first chapter where the authors lay out the setting and models of AIDS psychiatric care. They start with effective parenting and prevention of early childhood trauma and conclude with the sections on education, HIV testing, condom distribution, rehabilitation centers, chronic care facilities and nursing homes. They touch upon the prejudice and discrimination labeled as AIDSism which unfortunately is ubiquitous and is also discussed in other chapters in the book.

Chapters titled Biopsychosocial Approach and HIV Through The Life Cycle cover material with which a psychiatrist trained in the past twenty-five years should be quite familiar. However the authors are not content with just reminding the reader to take a comprehensive history in areas relevant to this disease, but they offer over 100 suggested questions in doing a sexual history, suicide evaluation, substance abuse history or a violence evaluation. The following are examples of a few questions, which you may not have thought to use:

1. (Taking a sexual history) How do your cultural beliefs affect your sexuality?

2- Are you aware that petroleum-based lubricants (Vaseline and others) can cause leakage of condoms?

3- (To an LGBT person) What words do you prefer to describe your sexual identity?

4- (Evaluating suicidality) Do you plan to rejoin someone you lost?

5- (Taking a substance abuse history) What led to your first trying (the specific substance or substances)?

6- What effect did it have on the problem, crisis, or trauma in your life?

While it is stated that little is known about the relationship between aging and manifestations of psychiatric disorders in HIV positive persons, the discussion and questions raised about this topic in these chapters seem particularly important as treatment is now allowing people with AIDS to become senior citizens.

In the chapter titled Psychotherapeutic Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders it was noted that the enhanced understanding of the conflicts and struggles of the HIV positive patient afforded by psychodynamic psychotherapy has been described by multiple authors. This modality of treatment may be especially suited for patients with a trauma history as physical changes in the body and relationship stresses can awaken conflicts triggered by early trauma and neglect. This history of childhood emotional, physical and sexual trauma as well as neglect is also reported to be associated with risk behaviors and is prevalent in persons with HIV. Other major themes, which were identified, that could surface in psychodynamic work include fears about mortality with the erosion of defensive denial as the illness progresses and conflicts surrounding sexuality. There also was a review of interpersonal psychotherapy, CBT, spiritual focused care, and various group therapy formats.

The chapters on psychiatric aspects of stigma of HIV/ AIDS will also be of particular interest to the readers of this journal who are usually quite involved in dealing with subtle nuances in psychotherapy. Victim blaming, addict phobia and homophobia also called heterosexism are discussed in this context. While clinicians usually don’t have any trouble identifying stigma when they see it, there are scales which can be administered in both research protocols and clinical settings.

Dr. Cozza is the lead author in the chapter concerned with psychopharmacologic treatment issues. It is the longest chapter in the book and can best be summarized by their conclusion that the prescribing of psychotropic or any other class of medications to HIV positive patients taking ART is a complicated undertaking. The chapter provides an explanation of this statement in a narrative style as well as with some detailed tables showing the propensities of various medications to cause inhibition and induction.

Although psychiatrists are usually not involved with the treatment of physical symptoms or the actual administration of therapeutic drugs for medical conditions, if they work with patients with AIDS they will be discussing various symptoms and complications. Dr. Goforth and Cohen put together two chapters which clearly explain symptoms of AIDS, as well as the medical illnesses associated with them. They review fatigue, sleep disorders, appetite problems, nausea and vomiting with a complete differential diagnosis and intervention options. The full range of endocrine problems, dermatological disorders , HIV associated opthamalogical diseases, malignancies, liver and kidney disease as well as the potential symptoms of these conditions are covered.

The one chapter, which was written by four authors, was titled Palliative and Spiritual Care of Persons with HIV and AIDS. This not only covered a discussion of the management of pain, other physical symptoms, behavioral symptoms including violent behavior and suicidality but it offered a review of models for spiritual care. The work of Breitbart and colleagues with cancer patients using meaning centered interventions based on Victor Frankels ideas was introduced as was Kissane and colleagues description of a syndrome of “demoralization” in the terminally ill which is distinct from depression. It consists of a triad of hopelessness, loss of meaning and existential distress expressed as a desire for death. A treatment approach for this state is outlined. This chapter concludes with a review of the role of psychiatrists and other clinicians at the time of death and afterwards. This includes a discussion of anticipatory, acute and complicated grief.

Although HIV disease and AIDS is no longer the mysterious disease which people are afraid to talk about and healthcare workers dread seeing patients with, nevertheless it is a very serious illness which cuts across all specialties and has great relevance for psychiatrists and other mental health professionals. It is estimated that more than one million people are living with HIV in the USA. Even now with retroviral treatment available, this disease is expected to infect 90 million people in Africa resulting in a minimum of 18 million orphans. Needless to say, this book should be translated into many languages and should be available internationally. This book gives us a full background about AIDS and allows psychiatrists and other mental health professionals to have this fund of knowledge at our fingertips. Also, if and when there is another deadly virus that appears on the scene, our profession will have a model and a valuable compendium of how to approach it, which is something we did not have thirty years ago.

To purchase this book on Amazon, please click here

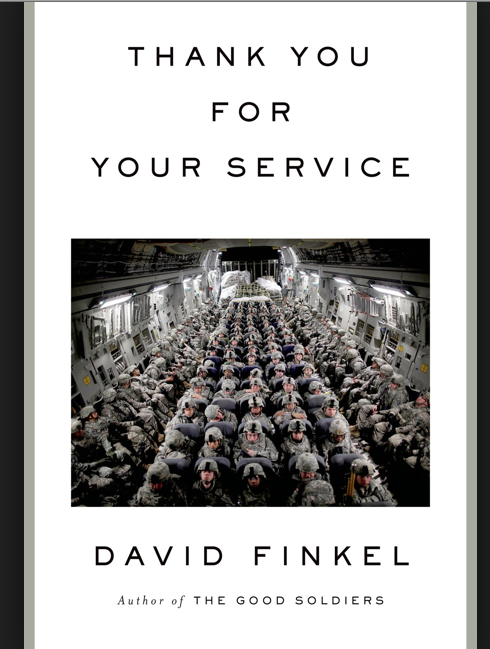

Thank You For Your Service by David Finkel– This is a nonfiction account, which reads more like a novel, of the story what happens to the soldiers who return from Iraq and Afghanistan after being mentally injured in combat. The author David Finkel previously wrote a well-received book, The Good Soldier, about his observations as an embedded war correspondent. Now he closely follows a group of soldiers most of whom know each other as they came home to their families, some with physical injuries but all with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He writes in the third person and there is no trace of the author’s actual presence although it is like he is a fly on the wall, reporting dialogue in their homes, bedrooms, etc. and in the various treatment programs, which attempt to rehabilitate them. The book takes us back to their combat experiences in foreign countries as well as to their battles with their spouses and with their demons. This is a close up view that can get you inside the head of these men and their spouses. It is as if you were the trusted therapist who was being told all. In fact, clinicians in training or those wanting to get experience with this population of people, psychologically impaired by war would certainly benefit by reading this book. There was clear insight into the thinking of all the subjects but there was no simple answer how to treat them or how they can live with the sequelae of this war experience.

Thank You For Your Service by David Finkel– This is a nonfiction account, which reads more like a novel, of the story what happens to the soldiers who return from Iraq and Afghanistan after being mentally injured in combat. The author David Finkel previously wrote a well-received book, The Good Soldier, about his observations as an embedded war correspondent. Now he closely follows a group of soldiers most of whom know each other as they came home to their families, some with physical injuries but all with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He writes in the third person and there is no trace of the author’s actual presence although it is like he is a fly on the wall, reporting dialogue in their homes, bedrooms, etc. and in the various treatment programs, which attempt to rehabilitate them. The book takes us back to their combat experiences in foreign countries as well as to their battles with their spouses and with their demons. This is a close up view that can get you inside the head of these men and their spouses. It is as if you were the trusted therapist who was being told all. In fact, clinicians in training or those wanting to get experience with this population of people, psychologically impaired by war would certainly benefit by reading this book. There was clear insight into the thinking of all the subjects but there was no simple answer how to treat them or how they can live with the sequelae of this war experience.

Ido in Autismland by Ido Kedar – Although I am not an expert in this area, I believe that this will be a landmark book for families, educators and any professionals who work with young people with autism. It is a book of short essays written by a 15 year old about his experience with his condition starting with some pieces written when he was 12 years old.

Ido in Autismland by Ido Kedar – Although I am not an expert in this area, I believe that this will be a landmark book for families, educators and any professionals who work with young people with autism. It is a book of short essays written by a 15 year old about his experience with his condition starting with some pieces written when he was 12 years old. Vienna Triangle

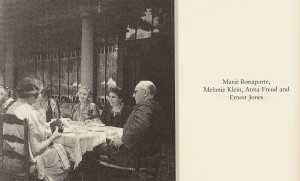

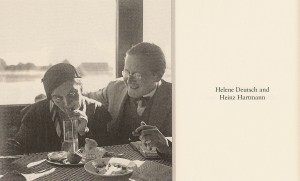

Vienna Triangle The year is 1968. Helene Deutsch is 84 and, while vacationing in Provincetown, Massachusetts, meets Kate, a young woman who, by coincidence, is writing her PhD thesis at Columbia University about the early women analysts. Dr. Deutsch is one of the most prominent, well-known and respected early women psychoanalysts and who had been in analysis with Sigmund Freud himself. One thing leads to another and in the course of their now mentoring relationship Kate uncovers some previously hidden documents belonging to her mother and which shed light on a family secret that her mother had withheld from her. This secret was that her maternal grandfather was the well-known psychoanalyst Victor Tausk who had been part of Freud’s inner circle and who had committed suicide.

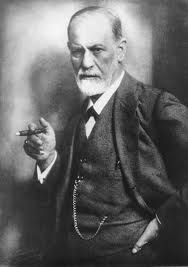

The year is 1968. Helene Deutsch is 84 and, while vacationing in Provincetown, Massachusetts, meets Kate, a young woman who, by coincidence, is writing her PhD thesis at Columbia University about the early women analysts. Dr. Deutsch is one of the most prominent, well-known and respected early women psychoanalysts and who had been in analysis with Sigmund Freud himself. One thing leads to another and in the course of their now mentoring relationship Kate uncovers some previously hidden documents belonging to her mother and which shed light on a family secret that her mother had withheld from her. This secret was that her maternal grandfather was the well-known psychoanalyst Victor Tausk who had been part of Freud’s inner circle and who had committed suicide. Author Brenda Webster uses this plot in her novel to explore and describe life in Vienna and the complicated interactions both inside and outside of Freud’s Inner Circle during the birth of psychoanalysis. The personalities of the cast of characters unfold. Freud the creator, the father figure, is portrayed as extremely protective of his newly developed “baby.” Tausk is described as a brilliant young man who is making important contributions to psychoanalysis but who feels he is not quite appreciated by the Master. He develops a love affair with Salome who at the same time has become one of Freud’s favorite pupils. Young Helene Deutsch is making her own contributions about psychoanalytic theory and women at the same time that she is having her own love affairs. Freud does not grant Tausk’s request to be analyzed by him and instead refers him for analysis to Deutsch. There is a question about whether Freud’s harsh and rejecting treatment of Tausk contributed to his decision to take his life. Documents that purport to show Freud’s reaction to his junior colleague’s suicide do not paint a flattering picture of the leader of the psychoanalytic movement.

Author Brenda Webster uses this plot in her novel to explore and describe life in Vienna and the complicated interactions both inside and outside of Freud’s Inner Circle during the birth of psychoanalysis. The personalities of the cast of characters unfold. Freud the creator, the father figure, is portrayed as extremely protective of his newly developed “baby.” Tausk is described as a brilliant young man who is making important contributions to psychoanalysis but who feels he is not quite appreciated by the Master. He develops a love affair with Salome who at the same time has become one of Freud’s favorite pupils. Young Helene Deutsch is making her own contributions about psychoanalytic theory and women at the same time that she is having her own love affairs. Freud does not grant Tausk’s request to be analyzed by him and instead refers him for analysis to Deutsch. There is a question about whether Freud’s harsh and rejecting treatment of Tausk contributed to his decision to take his life. Documents that purport to show Freud’s reaction to his junior colleague’s suicide do not paint a flattering picture of the leader of the psychoanalytic movement. The characters in this book are interesting and well developed. There is love, romance, jealousy, rivalry, narcissism, loyalty, rejection, dedication to the cause, and the mysterious suicide of Tausk that contribute to making this a fine novel. It is a page-turner (or in my case a button pusher – I read books on the Kindle). This book should have strong appeal to all students of psychoanalytic and psychodynamic theory. It is well known that to fully grasp all of these ideas you need to go back to the streets of Vienna and the lives of the people who were bringing forth this revolutionary new understanding of human behavior.

The characters in this book are interesting and well developed. There is love, romance, jealousy, rivalry, narcissism, loyalty, rejection, dedication to the cause, and the mysterious suicide of Tausk that contribute to making this a fine novel. It is a page-turner (or in my case a button pusher – I read books on the Kindle). This book should have strong appeal to all students of psychoanalytic and psychodynamic theory. It is well known that to fully grasp all of these ideas you need to go back to the streets of Vienna and the lives of the people who were bringing forth this revolutionary new understanding of human behavior. In the author’s afterword she further elaborates that an important letter mentioned in the book from Freud to Andreas-Salome after Tausk’s suicide is genuine, as are her responses to it. (This is one of the documents to which I referred to above.) Webster also cites Kurt Eissler’s writings that she says defended Freud’s treatment of Tausk. This suggests that she made efforts to found the main premise of the book on as much fact as possible.

In the author’s afterword she further elaborates that an important letter mentioned in the book from Freud to Andreas-Salome after Tausk’s suicide is genuine, as are her responses to it. (This is one of the documents to which I referred to above.) Webster also cites Kurt Eissler’s writings that she says defended Freud’s treatment of Tausk. This suggests that she made efforts to found the main premise of the book on as much fact as possible. BW: I had written two previous books of psychoanalytic criticism and a memoir chronicling my history in therapy and had no intention of doing more. Then one day I was reading about how the great Goethe sucked the life out of people close to him and used them for his own purposes. This made me think of Freud and Viktor Tausk. I wondered if genius couldn’t tolerate the existence of great talent in its vicinity and I was off and running.

BW: I had written two previous books of psychoanalytic criticism and a memoir chronicling my history in therapy and had no intention of doing more. Then one day I was reading about how the great Goethe sucked the life out of people close to him and used them for his own purposes. This made me think of Freud and Viktor Tausk. I wondered if genius couldn’t tolerate the existence of great talent in its vicinity and I was off and running.

Handbook of AIDS Psychiatry by Mary Ann Cohen, Harold W. Goforth, Joseph Z. Lux, Sharon M. Batista, Sami Khalife, Kelly L. Cozza and Jocelyn Soffer, Oxford University Press, New York, 2010, 384pp, $49.95

Handbook of AIDS Psychiatry by Mary Ann Cohen, Harold W. Goforth, Joseph Z. Lux, Sharon M. Batista, Sami Khalife, Kelly L. Cozza and Jocelyn Soffer, Oxford University Press, New York, 2010, 384pp, $49.95